SUMMARY

As revealed by a slew of whistleblowers, the global surveillance infrastructure and the potential weaponisation of data has created a perverse atmosphere where privacy is just a figment of the imagination

With a ban on Huawei in the US and other parts of the world, and India’s ban on 200+ Chinese apps, countries around the world have taken steps to cut China’s influence on the global tech ecosystem to size

With privacy-ending surveillance on the rise, do we have adequate law to defend our privacy? Does the PDP Bill introduced in the parliament address our concerns, we asked Justice Srikrishna, the man behind the Bill

On the evening of June 29, Twitter came abuzz with news of India biting the bullet and banning 59 Chinese apps, including mega apps such as TikTok, Camscanner, shareIT, Helo, WeChat, Weibo as well as games like Clash of Legends.

While the government claimed that the decision to ban apps has been taken after considering months of feedback from concerned parties and citizens about data sovereignty, the timing of the ban — coming just weeks after the Chinese army’s incursion into the eastern Ladakh region — makes it a geopolitical.

The government said that the banned Chinese apps posed a “threat to sovereignty and integrity” of the country. A few weeks later, another 47 apps were banned, taking the list now to over 200.

For long, intelligence agencies around the world have accused Chinese tech companies of stealing user data to provide geopolitical advantage to China. And with its move, India joined the league of Western nations such as the US, UK, Canada and others that see China as a threat in the Global Data War.

Even before the ban on apps, India was on a mission to track the Chinese money coming into the tech industry and startups. With the amended FDI policies, there is increasing scrutiny on foreign direct investments from China. Thirdly, with the Vocal For Local call, the Indian government also targeted Chinese products and services being used by the various government departments.

But India didn’t make these decisions in isolation. And as we will see in many ways, the ban on apps and the scrutiny on Chinese money is part of a concerted global effort to stifle China’s dominion on the tech industry.

Using Huawei To Bite China

December 1, 2018, Buenos Aires: As US President Donald Trump dined with Chinese President Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the G20 Summit, presumably discussing trade between the two countries, little did they know that sitting next them, the White House national security adviser John Bolton was simultaneously orchestrating the arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou, the daughter of Huawei founder and chairman Ren Zenghfei would be detained at the Vancouver International Airport by the Canadian Border Services Agency and this would derail trade between US and China completely — the impact rippling across the global tech industry.

Since that day in December 2018, Wangzhou has been in house arrest at her Vancouver residence and facing extradition to the US on 29 counts mainly for sanction violations and stealing trade secrets. The detention immediately triggered the trade war between China and the US to another level and subsequent sanctions by the US only served to intensify it.

Along with Huawei, Chinese tech giants such as ZTE, drone maker DJI, app giant ByteDance and a slew of other Chinese companies are facing a phase out across the major markets in the world. Along with India, the US, the UK, Australia, the EU and other countries have also blocked Chinese companies from participating in major deals. The US department of commerce recently added 33 Chinese companies to its economic blacklist for helping China spy on its minority Uighur Muslim population in the Xinjiang region or because of their close ties with China’s government and military.

While Chinese companies are being phased out by India and other countries today, the suspicions on China go back many years. For instance, in 2012, cybersecurity company Trend Micro published a report which found Tencent employee Gu Kaiyuan behind carrying out a massive data espionage programme in India, Japan and Taiwan.

While the Chinese government disavowed Gu Kaiyuan, according to the New York Times, the techniques and the targets pointed to a state-sponsored campaign. Gu had apparently also recruited students to work on the university’s research involving computer attacks and defence.

Besides hacking Tibetan spiritual figurehead Dalai Lama’s emails, the group used malicious documents containing information on India’s ballistic missile defence programme to lure potential victims. It contained malicious code that exploited a vulnerability in Microsoft Office to drop trojan malware onto a compromised system which would then connect to a command and control server.

According to an India Today report, as the India-China border dispute escalated, there have been thousands of such attacks on various NIC-hosted websites which have been thwarted. “Many of the known hackers are established fronts of the Chinese government,” said an IT ministry official.

China’s Control On Indian Tech And The 5G Question

Beyond its aggression at the Indian border, China’s strategy is about targeting the economy and the tech industry, in particular, believe cybersecurity experts. With investments in most major tech startups and slowly tightening its grip over vital sectors such as banking, media & entertainment, edtech, construction and pharma, China has been able to not only monitor India’s market and tech developments but is also controlling it in a way, claim experts.

Even beyond their investments in major sectors, Chinese companies have a huge consumer base in India too. Majority of Indian internet users use Chinese-brand smartphones such as Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, OnePlus or Honor, and Chinese apps such as PUBG, TikTok, Clash Of Legends, ShareIT, CamScanner and so on are some of the most popular apps in India.

Being smartphone-oriented, the data generated by all of these apps is first-hand and gives a collective picture of the Indian internet consumer, including but not limited to:

- The apps being used by Indians, including fintech apps and credit data through SMSes

- User behaviour and data consumption

- Product preference for Indian consumers

- Demographic data for any given area

- Location activity for any user and more

This would allow any authority with centralised access to this data the ability to create a profile for each Indian user and then use it for advertising purposes, sales or for political interests and control.

Speaking to Inc42, former Infosys CFO and partner, Aarin Capital Mohandas Pai had earlier indicated that China is also trying to control the technology developments and its market in India.

“Many of the startups which have Chinese investments today hold their board meetings in China. There is no clarity over where the data is stored. Is our data going to China, we don’t know. So, the Chinese influence is very strong. And, that’s why we may need such policies,” — Pai said.

Chinese companies do not have a choice if the government of the day there asks them to handover all the data.

According to Article 14 of National Intelligence Law of China it is mandatory for Chinese to provide necessary support, assistance and cooperation if required by Chinese intelligence agencies.

None of the Chinese companies such as Huawei, ByteDance or others have ever admitted that the data is being shared with Beijing. The Indian government also asked all of its departments to cancel the contracts with Chinese companies that are under process. Following India’s ban on over 106 Chinese apps, the US, UK, Australia and many other countries too have taken similar actions to cut China to the size.

Speaking to Inc42, Menny Barzilay, Tel Aviv-based cybersecurity strategist and former CISO said, “Companies share data with governments. That’s an established fact. And it happens everywhere. This is almost impossible to change. Our options will either be creating a global treaty in which all countries commit not to take information from business companies, or create global peace so data collection will not be relevant anymore. I’m sure everyone understands that the chances for each to happen are not that great.”

In 2020, the most prominent reason for the ongoing data war is the advent of 5G and China’s lead in this matter which gives the companies an obvious edge, given the cost-effectiveness they offer. The importance of 5G could be understood by the fact that simply the construction of 5G networks will require an estimated investment of over $2.7 Tn globally in 2020 alone. Though in India’s case, 5G might take at least a few years to reach penetration, the government is looking to forge a China-free 5G future given recent statements.

But here’s the thing, the current wave of data protectionism around the world and the attack on China might have been positioned as in the interest of the greater good, but there’s no hesitation among governments to use the same techniques and even greater surveillance powers to spy on citizens. So while publicly political leaders have proclaimed war on data theft and rampant data sharing, in private, they are also waging a war on privacy.

Privacy Begins At Home

Unlike the past, when war made everyday life perilous, this slow-burning data war requires citizens to be asleep to the fact that there is indeed a war going on. The Five Eyes nations, India, China, Pakistan, Israel, Russia and many other countries have been engaged in a prolonged war for decades. The notion that the cold war is over is a myth. In the modern world, while armed conflicts will likely be avoided, it’s impossible to avoid the information wars. Banning apps is like trying to plug a massive hole in the boat with a finger, and the irony is that the hole was created by the same people trying to seemingly keep the boat afloat.

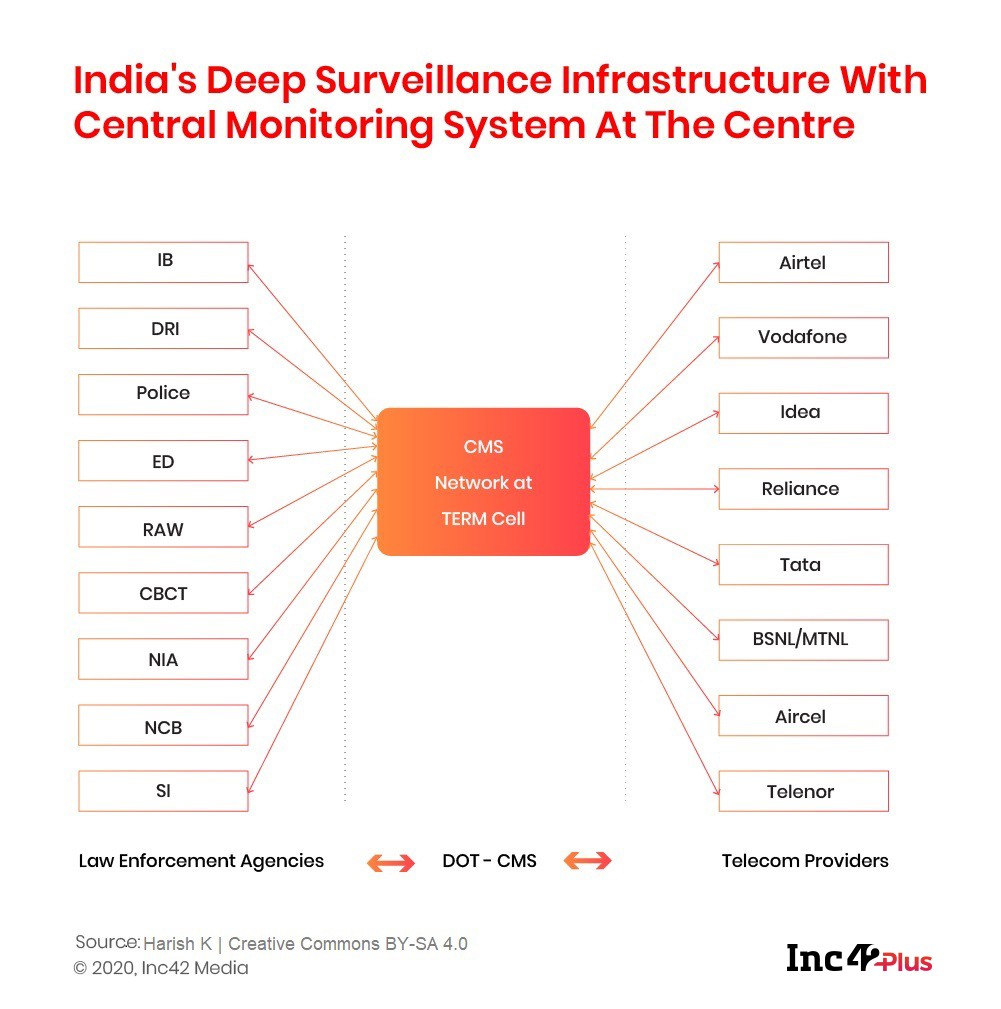

In India, after years of planning, the government set up the Centralised Monitoring System in 2015 to automate the process of lawful interception and monitoring of telecommunications. Put simply, it was about surveillance of Indian citizens. So how many phones are being tapped just by the central government? Journalist Saikat Dutta tweeted in 2018.

“A few years ago I filed an RTI asking how many phones are tapped at the federal/central level annually? The answer, under RTI from MHA: 100,000!”

While the Indian government didn’t produce the actual number of current phone taps when asked in the Rajya Sabha on November 20, 2019, the bigger question is — are the concerned authorities following the due notification process in every case?

Well, that’s just about phone tapping. In 2018, India’s home affairs ministry had also authorised ten central agencies and bodies to intercept, monitor, and decrypt any information generated, transmitted, received or stored in any computer under the Section 69 (1) of the Information Technology Act, 2000 and Rule 4 of the Information Technology (Procedure and safeguard for Monitoring and Collecting Traffic Data or Information) Rules.

And then there’s Aadhaar — which if we extended metaphor of a leaky boat should have sunk by now — but somehow Aadhaar data continues to be plundered in the name of providing services and then being left out in the open for others to use and abuse.

While in 2020, the government is cracking down on Chinese apps and investors with the express intention of protecting the data sovereignty of India, it’s actually the same data which the Indian government is looking to intercept and monitor. This twist of irony brings up the oft-asked question — can freedom and security co-exist without either getting diluted?

How The Wild West Killed Privacy

Before India’s CMS and other surveillance programmes, the fight for online privacy and against global surveillance began with something no one saw coming. Just over seven years ago, on June 6, 2013, a pair of seemingly innocuous news stories were published simultaneously in The Guardian in the UK and the Washington Post in the US.

Based on information obtained from the same source, the two reports spoke about rampant spying on US citizens by the country’s government in collusion with telecom carriers. A few days later, the source came forward and identified himself as Edward Snowden, a contractor for the National Security Agency, who had leaked a treasure trove of documents detailing the tactics, strategy and technology used by the most powerful governments in the world to spy on everyone — without exception.

While Snowden is often credited as the man who set the discourse around privacy, it was Julian Assange-founded Wikileaks which encouraged whistleblowers the world over like Reality Leigh Winner, Katherine Gun and Chelsea Manning in getting secret documents out, besides Snowden.

These leaks and the exposes immediately set the discourse to drawing a line between the right to privacy and the authorised power of intelligence agencies eroding it under the garb of the war against terror. And many of these practices have been passed on to allies such as India to set up their own surveillance systems.

If at the crux of the government surveillance programmes is control over citizens and national security even at the cost of excessive spying, then corporate interests are aligned with data and using it to sell more and earn more money. The two interests have aligned in many ways over the past few years.

The most prominent example came in 2018, when the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal further exposed the ocean model that was used to change people’s minds during the US presidential elections, especially those considered swing votes. This startling revelation made it clear that not only are governments snooping on citizens, keeping an eye on everything online, but are also weaponising the very same data to use against the citizens.

It’s not just the US — Cambridge Analytica offered its services all over the world, including India, and today operates under the name Emerdata, after Cambridge Analytica was forced to wind down its business in the wake of global inquiries.

Data that helps build a deeper effective AI can also be weaponised by those with vested interests, to the extent that Tesla founder Elon Musk had said back in 2014, “AI is potentially more dangerous than nukes.”

After being one of the founding members of the open source OpenAI programme in 2015, Musk walked away over supposed ethical reasons. However, OpenAI has continued its work and as shown through the release of the Generative Pre-training Transformer-3 (GPT-3), it has taken things to the next level.

Clearly, the revelations of the global data surveillance infrastructure and the potential weaponisation of the data has had a cataclysmic effect on the global internet ecosystem and the current wave of data protectionism, anti-globalisation sentiments around tech products and services. But among a certain class of experts, activists and political leaders, the debate is centred around data protection and more stringent privacy laws. Who will win this round?

Expanding India’s Central Monitoring System

Recently, India has been looking to bolster its various security arms with technology being at the centre of all plans. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) has floated a fresh request for proposals for an automatic face recognition system (AFRS), a centralised web application hosted at the NCRB Data Centre in Delhi with DR (Disaster Recovery). This will be made available for access to all the police stations of the country.

Explaining the architecture of CMS, National Cyber Security Coordinator Lt Gen Rajesh Pant told Medianama, “The aim is to advise this Council in overseeing and compliance of all the cybersecurity aspects including implementation of action plans in cybersecurity by the nodal agencies, evaluation and analysis of incidents, then forming incident response monitoring teams. There’s a training part also. There’s an aspect of international forums and providing consultation and guidance to state governments. And also engage with the private industry for the formulation of policies.”

The latest developments related to policies such as the draft Personal Data Protection Bill will only empower the government to fetch one’s personal data at any time, even without consent, in the case of law enforcement agencies.

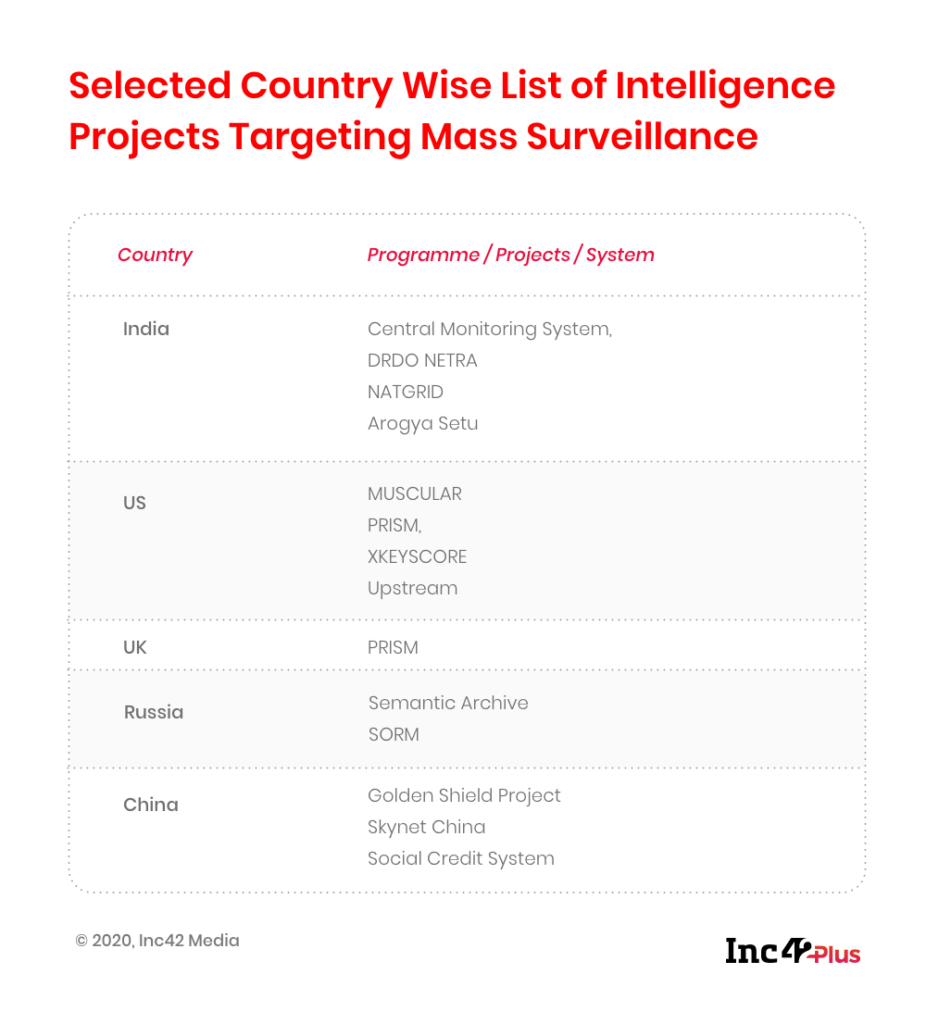

However, when it comes to global practices of mass surveillance, India is far behind the US, the UK, Russia and China. And in the global scheme of things, India is somewhat subservient to these powerhouses — an enabler rather than a controller.

To understand why this is, one must view each nation’s surveillance efforts not as an isolated measure, but part of the larger scheme of things. Not only is the Indian government monitoring Indian citizens, it is also sharing this information with other countries as part of the surveillance collaboration between nations. But within this cartel-like structure, there are power layers and India has not been in the most powerful layer — which is perhaps fast-changing.

With Reliance Jio making moves to enter Western markets as well as looking at an IPO in the US, the power dynamics in the global surveillance nexus are likely to shift in the near future and favour India. Jio has also earned the badge of being a clean telco from the US, which again might allow India to have greater say on the table.

The intelligence agencies of countries across the world have been monitoring influential persons and collecting information about them for decades. If China has been allegedly hacking the emails and private calls of the Dalai Lama, in the past, great personalities such as Albert Einstein, Charlie Chaplin and Martin Luther King Jr were constantly under scrutiny in the US and UK.

In the excellent, “The Einstein File: J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret War Against the World’s Most Famous Scientist”, Fred Jerome goes into detail on how the FBI in the US kept an eye on Einstein, which included tapping his phone calls. The aim was to somehow link him with communism and hence malign his credibility by calling him an agent of Russia. By the time Einstein died, the FBI had a 1,427-page dossier on him alone.

If the online data of citizens today is ever memorialised on print, it would take up a lot more than 1,427 pages for each individual, let alone public personalities.

The Pegasus WhatsApp spyware from Israel made a huge uproar worldwide including India. The spyware which secretly extracts a user’s private data, including passwords, contact lists, calendar events, text messages, and even voice calls was targeting over 1,400 people globally and 121 people in India, as confirmed by Facebook last year. This may have included the world’s richest man Jeff Bezos — if the rich and powerful cannot avoid surveillance, what hope do plebs have?

What’s interesting is that the NSO Group, the spyware maker, later clarified that the spyware is only sold to government authorities. And soon after, pretty much every government came down hard on the company.

Barzilay said that it is more than the war on information. It is a war on our reality. Today, governments and global enterprises understand the true power in data. With the right data-driven algorithms, various actors can manipulate people’s perceptions and opinions.

Will Law Catch Up To Tech And Does It Even Matter?

Data is fast enabling an ecosystem of technologies — cryptography, ML, AI, IoT, and more — that are making people more malleable and easy to manipulate, but they have also given immense capabilities to the governments which they wield to get their way.

Meanwhile, the development of law and regulations, as it usually happens, is too slow to ensure stringent implementation and enforcement of privacy laws. In fact, the process is made so deliberately complicated with thousands of stakeholders involved, that by the time the law is passed, it’s not only outdated, but technology has far surpassed the limitations that the law was hoping to enforce.

India is no different from the US. There’s no privacy law here either to enshrine citizen’s privacy as a fundamental right. The draft Personal Data Protection Bill which in 2018 made quite a buzz among stakeholders, has had its teeth pulled out even before it was presented in the parliament for the discussion.

The allegation has come from none other than the chairman of its drafting committee Justice BN Srikrishna. Speaking to Inc42, Justice Srikrishna stated that there are at least five points which make the latest draft bill radically different from what was submitted initially.

“First and foremost what bothers me is the security part of it. What we had suggested was that the government access to an individual’s data in only extraordinary circumstances which must be specified by the Parliament. They have now changed it to the extent where the Government can any time access the data. That is very worrisome,” said Srikrishna.

Further, Justice Srikrishna added that the composition of the proposed Data Protection Authority has been diluted, the degree of autonomy has been reduced and made in the favour of the government.

“Although this is supposed to be a personal data protection act, they have also introduced one Section which says, non-personal data can also be accessed by the government. I don’t understand this. The draft itself is about Personal Data Protection, why would they bring in non-personal data without any context,” he said.

The Draft Personal Data Protection Bill Clause 91(2) says that the central government may, in consultation with the DPA, direct any data fiduciary or data processor to provide any personal data anonymised or other non-personal data to enable better targeting of delivery of services or formulation of evidence-based policies by the government, in such manner as may be prescribed.

The Aarogya Setu app has become another tool for the government to track anyone under the garb of Disaster Management Act, which Justice Srikrishna calls completely illegal.

But can’t there be a fine balance between privacy, innovation and mass surveillance?

Generally speaking, mass surveillance systems are built to protect people. The question is not whether we need these systems (we do), but what is the acceptable way to implement and use them, Barzilay said. On one hand, citizens have very high demands from our governments in terms of security to find terrorists and stop incidents. On the other hand, they get angry when governments use mass surveillance programmes.

“And here we go back to the question of ethics and the correct way to use data. It is important to understand that there are no right or wrong answers here. Everyone has their own views and perspective on what should be the balance between privacy and security. Some people value privacy more than anything. Others are concerned about their own safety,” Barzilay added.

The Focus On China Distracts From The Truth

There are communist governments like Chinese and North Korean which do what they do regardless of the worldview. Then there are ‘powerful demagogues’ in the name of great democracies like the US, the UK, and India where even if the government will be seen advocating for people’s right to privacy day and night, privately, the government would be commissioning some secret projects of mass surveillance — snooping on millions and millions to catch a few hundred.

One of the biggest justifications for giving intelligence agencies across the world, the unrestricted access to one’s personal data has been to stop big mishaps before it happens.

As noble as the intentions may be, the end result may become far removed from the original goal. Just take a look at China’s way of tackling religious tensions and conflict in the Xinjiang region. Many have compared the Chinese ‘re-education camps’ in this part of the country to the concentration camps run by Nazi Germany under Hitler in the second world war.

For over a decade, Xinjiang has been the most policed area in the world. The police have installed CCTVs at the front and back doors of almost all the houses. They have listed around 75 parameters which determine how religious a person is, among which are parameters such as storing food at home, having a quran at home and other basic necessities. Such people are then sent to detention camps which China calls re-education camps.

The detention camps are so horrendous that if you take more than the assigned two minutes in the toilet you will be treated with electric shocks and in return you have to say ‘Thank You Teacher, I won’t be late next time’, a former detainee was quoted saying in a BBC report.

As part of its mega surveillance project SKYNET, China has also installed voice recognition systems and face recognition systems to monitor people across the country. This was widely implemented to curb the Hong Kong protests.

But let’s face the truth, China is no different than India or the US. And of course the role of online data in cracking down on dissenters is well publicised in many other countries. The US ran detention centres at borders and jailed little children while separating them from their parents just to crack down on illegal immigration. It is also using flawed facial recognition tech in some cases to nab so-called criminals.

Similarly, India is building detention camps, too, for the hugely-controversial Citizenship Amendment Act and the National Registry of Citizens. The government has also been known to use facial recognition technology to apprehend protestors. If anything, India’s use of technology is unabashedly borrowed from China. So while the recent ban targets China, India is not above using tactics that China deploys domestically for tech-based surveillance.

The problem with the idea of focussing only on China or the US or India is that the truth is clearly not in sync with it. It is very much in the interest of governments and the global surveillance-industrial complex to keep monitoring going, and even if many citizens may not feel that their privacy has been trampled, the government-big tech nexus has reduced citizens to mere voters and consumers.

While fans of Orwellian literature might have hoped that the works were satire, many of the ideas are turning out to be very real. And, if that’s the new normal, words like democracy, privacy and the nature of wars need to be redefined.

With inputs from Nikhil Subramaniam